|

| Alexander Hamilton, Author of The Federalist No. 65 |

In many of my blogs and Huffington Post columns, most often in those concerning The Federalist Papers, my goal has always to enlighten my readers by simplifying the lessons, visions, and admonitions of The Papers’ principle authors, John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton. Of the three, Hamilton was the most prolific (Jay fell ill and produced only five of the 85 papers, while Madison authored 29, and Hamilton crafted 51), and, arguably, his contributions were among the most influential in illuminating the underpinnings of the Constitution under consideration by the people. Writing in Federalist No. 1, Hamilton hoped the series of papers would "…endeavor to give a satisfactory answer to all the objections which shall have made their appearance, that may seem to have any claim to your attention."

You have to understand that at the time the Constitution was being considered, there was quite a bit of pushback from anti-Constitutionalists. The anti-Constitutionalists were fearful of a strong federal government; they worried that the rights of states and of individuals would be trammeled or usurped by a zealous federal power center. Their supporting documents, known as the Anti-Federalist Papers, included support for a Bill of Rights, which Hamilton, in Federalist No. 84, opposed. Hamilton was concerned that such an addition to the Constitution would weaken, rather than strengthen, what he believed were rights already enshrined in the Constitution itself. He wrote:

“I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and in the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers which are not granted; and on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why for instance, should it be said, that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible pretense for claiming that power.”

In short, Hamilton believed all the necessary rights of America’s citizens were clearly defined and defended in the body of the Constitution, and that no tacked-on “Bill of Rights” would improve upon the Constitution itself.

In what I see as one of the teachable examples of political compromise, if not grace in the face of loss, Hamilton’s argument did not win out, and Madison, who was a proponent of a Bill of Rights (more, in fact, than were eventually adopted), offered them up for inclusion in June, 1789.

But this essay is not about the Bill of Rights—that debate only illustrates the hard work, often contentious but ultimately affirmed, taken on by the Founders. This essay is about the fears of the Founders that unscrupulous office-holders, or candidates for office, if left unchecked by a strong Constitution and an independent Judiciary, would eventually anoint themselves unchallenged dictators, if not God-blessed sovereigns, by an ignorant public’s acclaim.

One of Hamilton’s premier biographers, Ron Chernow, published an essay titled, “Hamilton pushed for impeachment powers. Trump is what he had in mind” in the October 18 edition of The Washington Post (available in Sunday’s Outlook), in which he makes an eloquent, if not sobering, case for Hamilton’s vision for our current state of political affairs.

Chernow writes, “So haunted was Hamilton by this specter that he conjured it up in “The Federalist” No. 1, warning that “a dangerous ambition more often lurks behind the specious mask of zeal for the rights of the people than under the forbidden appearance of zeal for the firmness and efficiency of government. History will teach us that . . . of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants.”

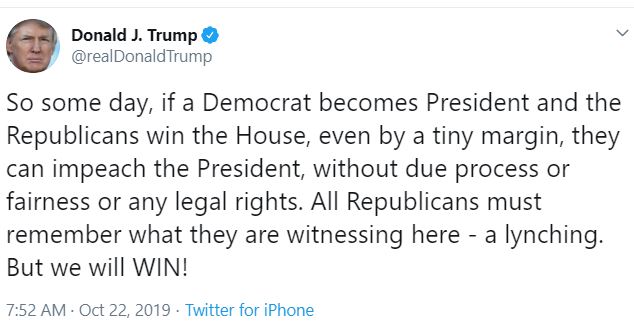

Chernow continues, “Throughout history, despots have tended to be silent, crafty and secretive. Hamilton was more concerned with noisy, flamboyant figures, who would throw dust in voters’ eyes and veil their sinister designs behind it. These connoisseurs of chaos would employ a constant barrage of verbiage to cloud issues and blur moral lines. Such hobgoblins of Hamilton’s imagination bear an eerie resemblance to the current occupant of the White House, with his tweets, double talk and inflammatory rhetoric at rallies.”

And of course Chernow is right, just as the Founders were right. Here is Chernow’s Clarion call:

“While under siege from opponents as treasury secretary, Hamilton sketched out the type of charlatan who would most threaten the republic: “When a man unprincipled in private life[,] desperate in his fortune, bold in his temper . . . despotic in his ordinary demeanour — known to have scoffed in private at the principles of liberty — when such a man is seen to mount the hobby horse of popularity — to join in the cry of danger to liberty — to take every opportunity of embarrassing the General Government & bringing it under suspicion — to flatter and fall in with all the non sense of the zealots of the day — It may justly be suspected that his object is to throw things into confusion that he may ‘ride the storm and direct the whirlwind.’ ”

Chernow concludes, “Given the way Trump has broadcast suspicions about the CIA, the FBI, the diplomatic corps, senior civil servants and the “deep state,” Hamilton’s warning about those who would seek to discredit the government as prelude to a possible autocracy seems prophetic.”

In a series of The Federalist Papers essays I wrote in the Huffington Post in 2017, I directed my columns to the Trump presidency, with warnings (never heeded) that his mindless course of action, via the rat-infested sewer pipes of deceit, hubris, and disdain for the rule of law and public opinion would run him afoul of every positive tenet of good government, citizen trust, and international comity enshrined in the words of the Founders.

I have posted recently, and several times in the past, essays and comments about my fear for the future of America. I have stated, without court-worthy evidence but with clearly-tuned emotion based on seven decades of life in our homeland and 35 years of service in the federal government, that our ship of state is, at the present time, steaming toward the edge of the rational map of public discourse and responsible actions where once the uncharted western world was labeled, “Here there be dragons.”

What actions can we, as passengers on this tempest-tossed, wildly careening, insanely-captained vessel of democracy take before we are driven onto the rocks of Constitutional destruction, thence to be devoured by our hungry domestic and foreign enemies? The obvious answer is “take back the helm,” but I will tell you, as a non-sailor who barely knows the difference between a scupper and a sheet, removing only the captain is not the solution—In this day of political hyperfactionalism, it is not even the problem.

In Federalist No. 65, Hamilton wrestled with the concept of impeachment by the House and removal by the Senate. He considered the fallibility of men—the ever-present temptations of self-promotion, undue enrichment, bribed biases, and ethical estrangement from faithfulness to a higher cause. He offered this conundrum (italics mine):

“The delicacy and magnitude of a trust which so deeply concerns the political reputation and existence of every man engaged in the administration of public affairs, speak for themselves. The difficulty of placing it rightly, in a government resting entirely on the basis of periodical elections, will as readily be perceived, when it is considered that the most conspicuous characters in it will, from that circumstance, be too often the leaders or the tools of the most cunning or the most numerous faction, and on this account, can hardly be expected to possess the requisite neutrality towards those whose conduct may be the subject of scrutiny.”

“The convention, it appears, thought the Senate the most fit depositary of this important trust. Those who can best discern the intrinsic difficulty of the thing, will be least hasty in condemning that opinion, and will be most inclined to allow due weight to the arguments which may be supposed to have produced it.”

"Where else than in the Senate could have been found a tribunal sufficiently dignified, or sufficiently independent? What other body would be likely to feel CONFIDENCE ENOUGH IN ITS OWN SITUATION, to preserve, unawed and uninfluenced, the necessary impartiality between an INDIVIDUAL accused, and the REPRESENTATIVES OF THE PEOPLE, HIS ACCUSERS?”

Here Hamilton was describing the possibility that popularly elected officials (at the time, Members of the House of Representatives) could, over time, yield to improper influences that would shade their objectivity and cause them to be biased judges during an impeachment session. He also considered that a large majority of impeachment pre-disposed representatives (tools of the most cunning or the most numerous faction) would skew the fairness curve and thus ignore or disregard a defendant’s appeals for a fair hearing. So Hamilton untangled this Gordian knot and explained to the readers of The Federalist No. 65 the reason for adding the Senate to the other side of the impeachment rope:

But here is where Hamilton, the Constitution, and I diverge, though I have no legal standing to opine with any legitimacy: In 1788, when both the proposed House and Senate were small—as was the nation itself—and the complexity of the machine of government was manageable by a few leaders, the idea of a Senate capable of unbiased judgement (those who can best discern the intrinsic difficulty of the thing) is quaint and almost laughable compared to the factionalism and Rubik’s Cube contortions of today’s upper chamber. But he goes on to proclaim the purest merits of the Senate as an impeachment jury:

“What, it may be asked, is the true spirit of the institution itself? Is it not designed as a method of NATIONAL INQUEST [sic] into the conduct of public men? If this be the design of it, who can so properly be the inquisitors for the nation as the representatives of the nation themselves? It is not disputed that the power of originating the inquiry, or, in other words, of preferring the impeachment, ought to be lodged in the hands of one branch of the legislative body. Will not the reasons which indicate the propriety of this arrangement strongly plead for an admission of the other branch of that body to a share of the inquiry?

Hamilton’s explanation of the best of two roughly irreconcilable legislative worlds tell us how hard it was for the Founders to find an equitable path to impeachment…but how important it was that such a path be forged to bring down a man such as Donald Trump.

Of course, the Constitution as approved by the people enshrined in Article I the powers of the House and the Senate to prosecute a president impeachment, but I am not convinced that the Senate Hamilton and the Constitutional signers envisioned is anywhere close to “a tribunal sufficiently dignified, or sufficiently independent.”

As long as both House and Senate are composed of nearly unbeatable majorities of disparate parties and factions, each with its own view of independence, fairness, equity, and due process, any impeachment of this, or any president, is guaranteed to fail in removal of a president whose party holds the Senate majority.

In my world, the House and the Senate would consist of men and women of great character, unblemished by outside factions, money, influence, and they would be chosen from equitably-adjusted districts (no Gerrymandering). Men like Mitch McConnell would never have so much power as to become anointed bullies, and the House would be devoid of special-interest caucuses capable of threatening leadership with unreasonable demands at the peril of legislative defeat.

My vote in 2020 will be for the man or woman I believe has the best chance of rising to the challenge of my impossible formula, and for state legislators who will fight the good fight against Gerrymandering. Only when factional corruption is checked and balance is achieved will the Constitutional processes envisioned by the Founders regain control of a ship that is headed ever closer to the dragons.

Hamilton, in reply to my blue-sky dreams would say again (as he wrote in 1788):

“If mankind were to resolve to agree in no institution of government, until every part of it had been adjusted to the most exact standard of perfection, society would soon become a general scene of anarchy, and the world a desert. Where is the standard of perfection to be found? Who will undertake to unite the discordant opinions of a whole community, in the same judgment of it; and to prevail upon one conceited projector to renounce his INFALLIBLE criterion for the FALLIBLE criterion of his more CONCEITED NEIGHBOR?”

I believe we can find such people to undertake the job of changing our course, and I believe we can overcome the conceited projectors--the false captains--who threaten the future of our our children and our nation.