Bringing it all together. You've got the artwork, now what?

|

| Working with my designer, Charlotte Moore, we arrived at the cover for The Reluctant Dragon in stages, from sketch (far left), to the almost finished version. |

Topics in this blog:

- Sketching the cover

- Downloading and working with photos and art

- Specifications

- Rectangles to squares--a most important journey

- Using your own art or photographs

Just a reminder: this blog series is aimed at

narrators who have taken on the responsibility of creating the completed cover

for their public domain audiobooks, as is often the case with narrators working

with Listen2aBook. The material covered in these blogs is not restricted to

just one publisher, and there may be other publishers who welcome a complete

audiobook package—from narration, to mastering, to completed covers for

submission to Audible or another online audiobook distributors. I refer to

Listen2aBook because I’ve been successfully narrating for L2aB for more than a

year now, and I’ve enjoyed the total process of working with Steven Jay Cohen

who has helped me move my last five books to Audible.

In the last blog, I talked about finding

artwork, graphics, or photographs (or all three) suitable for the cover of your

public domain audiobook. Now it’s time to begin assembling the several

components of a memorable, sales-inspiring, cover.

Paper and Pencil

Sketch out your cover

with pencil and paper before you open up your design program. You don’t need to

be overly artsy or detailed at this stage; you’re just looking to organize your

thoughts and visualize the general cover design. Draw a good-sized square—I’d

recommend two squares per sheet of regular printer paper, so that’s two 5”x5”

squares—and quickly sketch in the basic shapes of the artwork you’re

considering for the cover. And I mean quickly.

Don’t obsess over the sketch.

You just want the key elements down on the paper so you can figure out the best

placement for the title and your own credit line. Keep in mind that your cover

needs to be distinguishable from a distance of three feet.

Tip #1: The

Yardstick Standard

Just for giggles, find a

yardstick and hold it up between your face and the screen on your laptop or

desktop monitor. Now, look at images or texts on the screen and see which ones

are easy to read or discern from a yard away, and which ones have elements too

small to pick out. If you have to strain to figure out what is actually in an

image, that tells you that your cover had better be easy to figure out from the

same distance.

Cocktail Napkin Trick

If all else fails, and

you get stuck on the drawing, pretend you’re at a restaurant or bar, and you’ve

got a minute or two to sketch an idea out for someone sitting with you at the

table. You grab a cocktail napkin or one of those square cork coasters, and

sketch the basics of the cover. That’s the designer’s version of the 30-second

elevator speech.

Squaring a Rectangle

You will find very

quickly that some of the elements you want to place within the square cover’s

borders are rectangles—like a sweeping landscape of mountains, or an image of a

spiral galaxy, or wide cityscape, or the full width grill of a car—and you will

have to make a decision: use the image as is, which will limit it in size on

your square (and make it harder to recognize in the Audible version); or crop

the image.

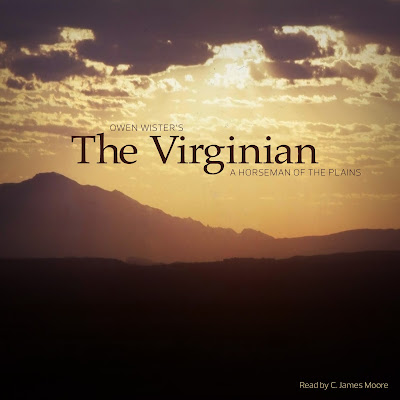

When I was designing the cover for The Virginian, I used a photograph I’d taken of the Front Range of

the Rocky Mountains at sunset. As you can see below, it is definitely a

rectangular image. But I really wanted to use it for the cover of the Western

novel, so I made the decision to lop off about a third of the right side of the

picture and a bit of the left to get to my square format.

One of the difficult parts of this cover was the font selection for the title. I worked closely with Brian Lee, a terrific designer in Raleigh, NC, to declutter my original font choice, and clean up the overall image. Brian's advice was to go with a classic font for the title, and drop the distracting graphics. In addition, he massaged the lower portion of the mountain picture to add an intensity to the darker areas that was lacking in the original. This is a classic example of how working with a designer can polish an otherwise amateur product.

One of the difficult parts of this cover was the font selection for the title. I worked closely with Brian Lee, a terrific designer in Raleigh, NC, to declutter my original font choice, and clean up the overall image. Brian's advice was to go with a classic font for the title, and drop the distracting graphics. In addition, he massaged the lower portion of the mountain picture to add an intensity to the darker areas that was lacking in the original. This is a classic example of how working with a designer can polish an otherwise amateur product.

|

| Three stages in the early layouts from a rectangular image, far left, to a square format. |

And here's the final cover as displayed on Audible

|

| This version is about as simple as I could get. |

If you really need the

entire rectangular element either because you are totally wedded to it, or because

any cropping would take away from its visual message, just understand that when

you place it, you will need to do something about the empty space that will

remain in the square. The solution could be as simple as putting in a

background color or pattern that works with the image, or using the open space

for your title and credits or additional images or art elements.

In the series of images below, I was trying to find one that would best portray key elements of the F. Scott Fitzgerald novel, This Side of Paradise, about a young man's journey from boyhood and Princeton, all the while navigating the tortuous world of love and loss. I had sketched out something that had one of Princeton's major buildings, but it was too tall and lacked a message by itself. Then I looked at drawings by C.D. Gibson, a noted artist of the time (famous for his Gibson Girls), and began narrowing my hunt until I found a horizontal panel that could be cropped to a tight square (final frame). By hand-coloring the image in Photoshop, and adding the title in a big, bold, shadowed font, my original idea became the Audible cover.

This exercise has three

benefits:

- It will simplify your thoughts about the cover;

- It forces you to work in a square;

- It will give you something to share with a designer should you go in that direction.

Although my own assembly workflow takes place

using Photoshop CC, the drag-and-drop and sizing techniques are pretty much universal

among graphic arts software—even basic ones. There are a couple of caveats, so

let’s deal with those right off the bat:

1. Image

Size. Big is not only good, it is required. That

tiny 147KB thumbnail image, with a resolution of 72 pixels per inch (ppi) you

pulled up in a Google search might work on your laptop screen, or on your

phone, but it will not stand up to Audible’s standards. Your completed cover is

going to be 2400 pixels by 2400 pixels at a minimum resolution of 100 ppi.

That’s a file that can range from 6-16MB, uncompressed, to anywhere from 1.5MB

to 4MB compressed as a jpeg. When you are selecting your art, think big; you

can always scale a photo or piece of artwork down from huge to modest, but you

can’t expect something tiny to withstand significant enlargement.

2. Resolution. Be consistent in image resolution. When you begin sizing your

photos or art, make sure all the elements you work with share the same ppi resolution.

All my cover art elements are 100 ppi images. If I were making the images for

sale as 20” x 40” posters, for example, the resolution would be much higher,

400 ppi at minimum, and probably much more. An audiobook cover is relatively

tiny compared to that, but it still has to stand on-screen scrutiny and be

readable from a distance of three feet. If you are working with a picture that

is 100 ppi that you place with an art image that is, say, 150 ppi, the two

elements will conflict with each other as you place them, scale them, or

otherwise manipulate them. Whether you choose 100 ppi or 150 ppi or higher,

stick to one resolution setting all the way through.

Tip #2: If you decide to work

with a designer, be sure to impart these directives about size and resolution

to him or her before they get started with their layouts. Few things will tick off a designer more than

finding out that there were standards that had to be met right at the

beginning.

Using your own art or

photographs—with one caution

There are no rules against using your own art or photographs for

your audiobook cover. The obvious advantage is that you own the work and are

thus exempt, to a point, from the whole copyright issue. To a point. You still

need to be very careful that your cover design, using your own photograph, does

not include recognizable images of living persons from whom you have not gotten

a model release. This means anyone who can be easily recognized in the photo—your

Aunt Sarah, your office baseball team colleagues, a woman standing by the Lincoln

Memorial in Washington, a photogenic Nebraska farmer, a colorful busker on a

street corner in L.A.—will have to agree, via a model release, to your use of

their image.

Let’s say you’ve just completed narrating a lovely book about

babies, and you decide that the cover would pop with that great picture you

took the other day of your neighbor’s six-month-old boy. Your neighbor loves

the idea, and says, “Sure, that’s a wonderful shot, go ahead.” Get it in

writing. I know Audible requires proof of a model release, and you should

proceed on the assumption that all publishers will require similar proof.

The other sticking point concerns recognizable properties with

logos or other trademark signs on them. A New York cityscape featuring many

buildings is pretty generic and probably okay to use on your cover; a picture

of a hot little café down in Greenwich Village, with the restaurant’s name over

the door, is subject to copyright and you need permission to use that picture

on your audiobook cover. Just use common sense; put yourself in the shoes of

the person whose picture you like, or the owner of the business you

photographed, and ask yourself if you would want that image to be out on the Internet

without written permission.

Coming Up Next

In the next installment of But What If I’m Write? I’ll address the

subject of titles and the typefaces (fonts) that can really draw a potential

buyer to your audiobook. You may not be able to change your audiobook’s title,

but you most certainly can give it the star treatment when it comes to laying

out your very own cover.